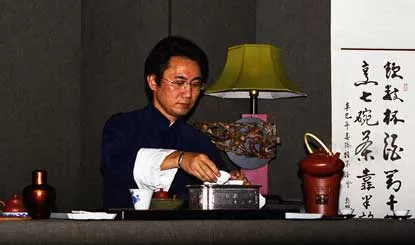

Song Dynasty Tea Culture

By/ Liu, Han-Chieh, founder of Chun Shui Tea Group

Published in / March 2016, 3rd Issue of “Chunshuier”

During the Spring Festival, while engrossed in the task of copying the Song Dynasty poems related to tea at home, out of nearly ten thousand excellent works, only about a hundred pieces touch upon tea, with less than one-third standing out. Upon closer examination, the content appears largely similar, with only a few variations in terms such as “dragon roasting”, “bamboo screen”, “snowy waves”, “mottled partridges”, “fair hands”, “powdered face”, “gentle breeze under both armpits”, and so on. This disparity may perplex those unfamiliar with the tea-drinking habits of the Song Dynasty. Even for those who understand, doubts may arise. How did they manage it? It seems they focused primarily on ceremonial offerings, which may not necessarily reflect the true essence of tea. Does this imply that other grades of tea were not considered authentic? What's even more peculiar is the constant inclusion of women in tea-drinking scenes, as if tea enjoyment was incomplete without their presence. While this aspect may be tolerable, it's more infuriating to consider the case of Tsai Shen, a scholar-official from Putian, Fujian. Despite rising to the esteemed position of “Grand Academician and Governor of Zhejiang”, not a single line in his two to three hundred poems, mostly revolving around romantic themes and women, mentions tea. This omission is particularly exasperating, given his origins in the homeland of tea.

To help everyone understand the subtle differences in tea poetry and what they talk about, I have selected two poems from thirty and provided explanations:

First poem:

“Returning Home” by Huang, Ting-Jian

Plucking mountains for the first round of Longtuan Tea,

Colors and fragrances exquisite,

As the grinding sound breaks the silence nearing dawn.

Crane avoids the smoke as it brews,

Dispelling sluggishness of mind,

Relieving worldly troubles,

Golden teapot flips snow-like waves.

Only worry that when night falls, the river flows into the sky,

Yet the lingering clarity stirs the night's rest.

Second poem:

“Unfolding Wash Stream Sands” by Zhou, Zi-Zhi

Freshly tapped from the mottled wall, Longtuan Tea emerges anew,

Crimson seals break as it simmers in the clear spring,

Intoxicated, cradling delicate twin bamboo shoots,

Like spotted partridges.

Snow-like waves splash, adorning golden threads,

Pine breeze awakens a jade-like visage,

Awaiting the subtle sweetness to linger on the lips,

Indulging in the moment.

Translated into colloquial language, the meanings are as follows:

First poem: Recently harvested tea leaves from the mountains are of good quality, they are ground into powder using a golden mill until late at night. The smoke from the charcoal stove scares away the walking crane. Drinking a bowl clears the mind and relieves fatigue. In the golden tea bowl floats the white foam of the tea. But one worries that as night falls, one will have to often answer the call of nature, leaving behind a night of restlessness.

The second poem: The verdant green tea cakes break easily. As the mountain spring water sealed with a red mark is boiled, the maiden holds the tea cup with beautiful hands, with patterns resembling partridge feathers. The foamy tea splashes, staining the golden threads of her clothes. The breeze from the pine tree awakens her beautiful face. Let's stay a bit longer, as good tea will gradually become sweet.

Is it clear now? In these two poems, the authors evoke imagery of indulgence and opulence, mentioning “Longtuan” (dragon tea cakes), women, golden mills, golden bowls, partridge-patterned bowls, golden threads, and even the presence of white cranes enjoying the good spring water. Their verses paint a picture of a life reminiscent of emperors and immortals, where luxury and refinement abound. As “Grand Scholar-Officials” and one serving as a “Prefect” while the other as a “Secretary to the Prime Minister”, their elevated positions might lead one to question whether such a life truly exists or if it is merely an aspirational fantasy. Nonetheless, their poetry transports readers to an idealized realm, free from worldly distractions, where the enjoyment of fine tea, exquisite wine, and captivating companions takes precedence. Interestingly, amidst their lavish descriptions, there is a sense of conscience apparent, as they include mentions of tea. This stands in stark contrast to Tsai Shen, who exclusively focuses on themes of romance and beauty in his verses.

During the Song Dynasty, spanning approximately four hundred years, the period is often referred to as the “Dian Cha Period”, signifying the predominant tea consumption practices, especially within the imperial court. However, diverse tea customs prevailed among the common people, with practices varying significantly from those of the Tang Dynasty era. Additionally, the tradition of brewing tea in large pots, which was widespread before the Wei, Jin, and Northern and Southern Dynasties, persisted beyond the capital city of Kaifeng, where tea was whisked in bowls to create frothy concoctions. While the imperial court favored golden and partridge-patterned bowls crafted from ox hair, the common folk typically used porcelain or earthenware bowls for their tea rituals. In the imperial palace, tea cakes were infused with spices, earning the moniker “Dragon Brain Fragrant Tea”, while among the common folk, the addition of honey transformed it into “Honey Fragrant Snow Waves”. Legend has it that in the city of Daming, a wealthy merchant seeking relief from the heat but enamored with tea, he innovatively incorporated snow from his cellar into his brew, thus becoming the pioneer of cold tea.

Away from the opulent realms of “Longtuan (Dragon Tea Cakes)”, “Golden Threads”, “Jade Hands”, and “Powdered Faces”, tea culture took on a more vibrant hue. In mountain temples, monks crafted homemade coarse cakes using simple stone mills and plain pottery bowls, yet their rituals exuded rich cultural significance. Regrettably, many of these practices were not meticulously documented, and even if they were, they often failed to find a place in the comprehensive Song Dynasty poetry collections. Hence, one can argue that the palace-centric portrayal of tea drinking in these collections merely scratches the surface of tea culture. To truly grasp its essence, the verses of Su, Dong-Po are preferred, for they depict real-life scenarios, rendering them more relatable.

In Song Dynasty poetry, romantic themes and notions of beauty frequently intertwine with references to tea, lending an air of artificiality that may confound later generations. It seems that in the realm of tea drinking, one is compelled to immerse oneself in romance, as if the act of savoring tea and living life were disparate realms, each governed by its own set of rules.

Su Shi, a celebrated figure of the Song Dynasty and an esteemed literary luminary for future generations offers profound insights into life through his tea poetry, shedding light on the tea culture of his time.

Among Su Shi's numerous tea poems, one of the most famous lines is perhaps, “Good tea is like a good woman”. This comparison suggests that good tea, like a good woman, should possess qualities of color, aroma, and taste. However, given the prevalence of tea and women-related poetry in Su Shi's era, such lines may risk being dismissed as mere trends or indicative of libertine inclinations. Su Shi's poetry covers a wide array of topics, including women, with remarkable candor. It is this openness that underscores his greatness. Here are four excerpts:

First poem [The Moon over the West River]

This year's Dragon Tea is unparalleled,

The Gulian Spring, a treasure since ancient times,

The teas of Xueya and Shuangjing offer an otherworldly aura,

The tea trees are from Beiyuan,

Brewing, it releases a milky allure, clear and pure,

Floating tea foam, light and round,

Who dares compete in this world?

Such as vying for the rouge-faced beauty behind the red window.

Second poem [Yearning for the South]

When the Spring is not yet old,

Soft wind gently kissing the swaying willows,

Come to the Transcending Tower with me,

To see the town’s blooms, embraced by the moat,

Gleaming through the misty rain so many homes. After the Hanshi Festival,

I woke up light-headed, turned over, and sighed.

Why am I nostalgic when surrounded by old friends?

Let's make a fresh fire raising the new tea for a toast.

How fine to spend our best years on wine and poems.

Third poem [Wanxisha]

Rustling, the cloth falls amidst the jujube flowers,

From south to north, the spinning wheel's whir,

Beneath ancient willows, farmers sell cucumbers,

Weary from wine, longing for sleep on the lengthy road,

As the sun climbs, thirst for tea consumes,

Knocking on doors, seeking shelter in the wilderness.

Fourth poem [Wanxisha]

Fine rain and a breeze, swaying, chill the morning air,

As willow branches outside the village burst with new buds.

Beside the Quan River, waters steadily rise,

White foam collects upon the dark bowl's surface.

Bamboo shoots and wild vegetables grace the plate,

In life's simplicity, profound flavor is found.

The poems can be interpreted as follows:

First poem

The small Longtuan tea cakes this year are of excellent quality. It's best to use the spring water from Gu Lian to brew them. The green tea from Xueya and Shuangjing is so good that it's like immortals descending to earth. Their variety originates from Wuyi Mountain in Fujian Province. The soup is snowy white, and the foam is light and round. What can compare to such a beautiful treasure? Except for the rosy cheeks of the maiden by the red window.

Second poem

Spring hasn't left yet, the breeze is gentle, willows sway. I climb to a tranquil spot to ease my mind today. Spring water flows, wildflowers bloom in the rain's misty veil, Though Cold Food Festival's over, wine with old friends prevails. Missing home, I sigh, but dwelling won't do any good, New tea's here. Let's brew it fast, as we should!

Third poem

The jujube flowers are in bloom, covering the clothes of passersby. The sound of spinning wheels fills the villages north and south. A rural couple sells cucumbers under an old tree. After drinking too much, and traveling too far, people feel drowsy. The sun beats down, causing heads to ache. Thoughts turn to the refreshing taste of tea. Eating cucumbers won't quench the thirst. By the roadside, there is a household. Let's go and see if they have any good tea to drink.

Fourth poem

The gentle rain and wind chill the morning air, while willow branches outside the village bud anew. Along the riverbank, the water level rises, forming white foam atop the black bowls. A dish brims with bamboo shoots and wild vegetables, where life's simplicity adds flavor.

Of the four poems, only the first alludes to the comparison of tea to the beauty of a young lady by the red window, likely his beloved wife, Madam Su. The others delve into themes of life, seasons, friendships, and hometowns. Through his verses, we glimpse real social experiences, Su Shi's struggles with tea addiction, and his philosophical musings on life. Though he doesn't explicitly focus on tea, it naturally weaves into the fabric of life. Such a scholar commands admiration and respect.

From the time of Shennong's discovery of tea until the Song Dynasty, tea transitioned from a life-saving elixir to a cherished companion of humanity. Yet, during the Song Dynasty, many misconceptions arose. For instance, a literary giant, Ouyang Xiu received a rare tea cake from the emperor but couldn't bring himself to enjoy it, allowing it to spoil and instructing his descendants to treasure it. While he may excel as a minister, he fails at appreciating tea. A true tea aficionado understands timing and the importance of sharing. So, let's pause a moment, select fine tea, gather good friends, and savor it with pure water and elegant teaware.

Let's heed the scholar's wisdom: “Try new tea with new fire; the true joy of life lies in savoring its flavors”.